Future's Tense

Featured in Lobby Journal #2 (The Clairvoyance Issue)

Page 33

Summer 2016

With Kyle Branchesi

“...Thus, a certain history of tastes will come to be inscribed in this project… More precisely, it will be… a way of talking about my work, about my history and preoccupation, an attempt to grasp something pertaining to my experience, not at the level of its remote reflections, but at the very point where it emerges.”

- Georges Perec, Notes Concerning the Objects That Are on My Work Table

When describing the potential qualities of their work, architects typically prefer the future tense (it will be 1776 feet tall, they are going to incorporate the principle of mass-production…). Models and drawings allow the architect to assume a unique position of foresight, but these presentation tools would seem to amount to little without the accompaniment of a language that argues for their full size versions in some distant future.

While architectural presentation has historically used the future tense, writing has famously practiced the opposite with the past tense (Mr. Bloom looked upon his sigh, glowing wine on his palate lingered swallowed…). This method conveys realism by describing a carefully chosen sequence of events, leading to either the present or alternate present. Even The Time Machine, a book that travels roughly 30 million years ahead of our own time, presents its story from the empiricism of a restful conclusion. The past tense is cool, calm, and collected; the future tense appears convoluted and shows signs of insecurity.

Writing rarely makes promises about the future, and at most ruminates over possibilities. Yet Georges Perec is a rare example of a writer that writes like an architect talks, guiding with almost as many “will be’s” and “going to’s” as an architect’s proposal for a tower and its considered influence over a neighborhood. His writing on “The Page” treats three half spreads like a developer treats land, constantly anticipating the future as it appears on the very next sentence. His words seem to be the masters of their own fate, but this was only possible when he could oversee their treatment on the final editing board. Otherwise, when trying to satisfy a second party, writing about architecture takes as much clairvoyance as it does to produce it.

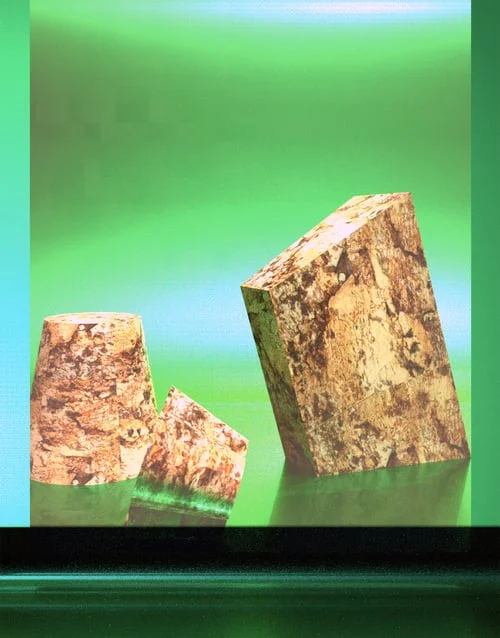

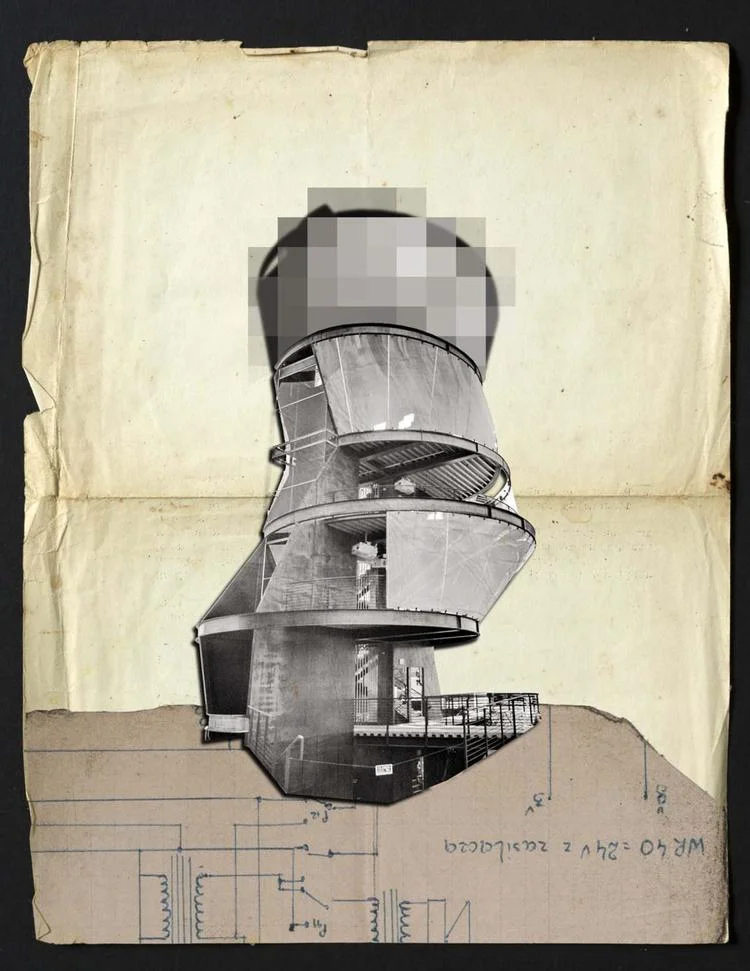

In submitting these words, the mix of vision and unease that comes with the future tense will also be applied: I can only guess how this writing will occupy the spread it will be assigned to, or if the very piece of paper this is written on has another author’s writing on the other side, possibly contradicting my own. This text is currently in one column a little under seven inches wide, but elsewhere it might be broken into two, one larger than the other (perhaps the break will start with “writing rarely makes promises…”). And as for the accompanying image, I can’t be sure that it will maintain the saturation level visible on the computer screen, let alone the correct sizing or proportions. Any alteration, as it goes from one pair of hands to another, could either strengthen its message or place it in jeopardy.

An unguessable transaction between parties is not unique to architecture, but, with the exception of a writer like Perec, the use of the future tense as a coping strategy might be. Those involved must know that a place can be a different place within the time a building is planned and a plan is built, yet a more considerate use of our inherited tense will make the future seem more clear.